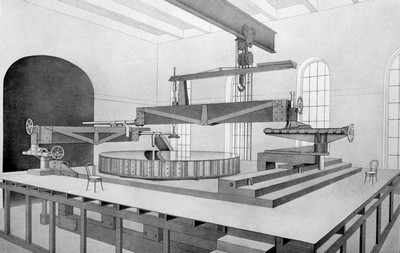

As often in sciences and technology, Leonardo da Vinci was a pioneer, creating machines for the production of optical devices. Indeed, between 1513 and 1517, he imagined machines to grind and polish telescope mirrors, which, at the time, were made of bronze. Unfortunately, it seems that, during his life, Leonardo da Vinci didn’t actually build his invention, as he often did with other inventions.

|

|

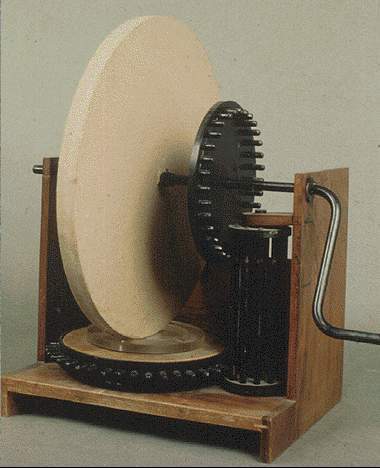

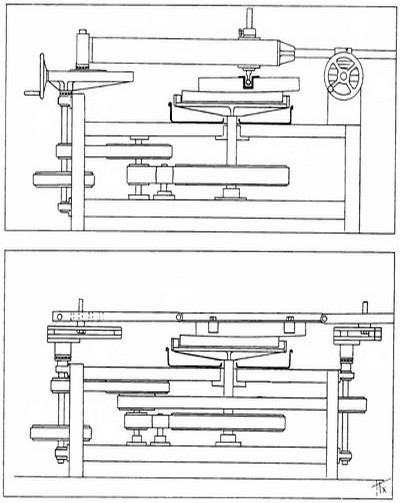

| Model of the machine imagined by Leonardo da Vinci to grind mirrors |

Model of the machine imagined by Leonardo da Vinci to polish mirrors |

In the early 17th century, progress in the theory of optics and mastery in the production of quality glass led to the development, especially in Italy, of craftsmen specialized in the making of lenses for medical glasses, microscopes, field glasses, refractors… At the time, specific tools were invented to facilitate the work of opticians, in particular machines whose principles were developed by Descartes, Huygens, Hooke, Helvelius, Cherubin d’Orleans and others.

|

|

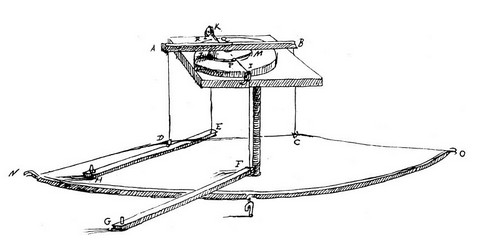

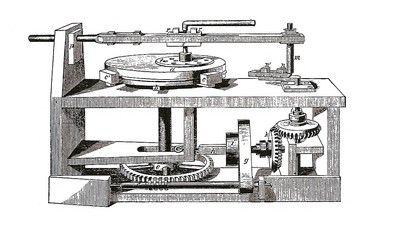

| Drawing by Huygens representing his lens polishing machine (1683) | Drawing of a machine to « hollow shapes » as imagined by Cherubin d’Orleans (1670) |

During that period until the end of the 19th century, the refractor had been dominant since Galileo had made it famous. Leonardo da Vinci’s idea of using a mirror to build an astronomical instrument remained ignored until Jacques Grégory (1663) first, later followed by Isaac Newton, revived it with the reflecting telescopes that still bear their names, even today. The first telescope mirrors were small bronze disks that were handshaped. But once they reached wider dimensions it soon became indispensable to use machines to shape and polish them. In this historical evolution the first amateurs were the most famous astronomers.

As early as 1788, William Herschel (1738-1822) built a polishing machine that allowed him to complete a 50′ mirror, in 1789. Unfortunately there is no description left of this machine that William Herschel kept secret until his death. He only says that its fabrication was necessary to replace the number of workers necessary to complete his larger mirrors, a number that would, at times, amount to a dozen men. Yet, a small polishing machine of his making can be seen at his museum in Bath , England (see photo below).

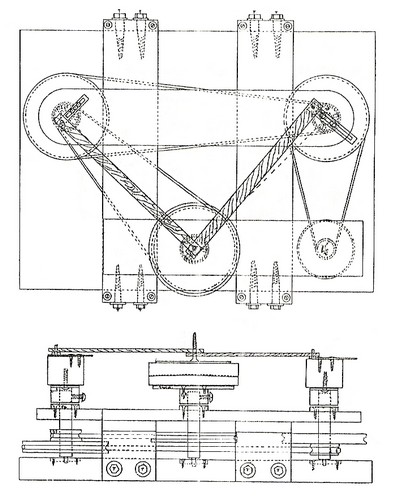

In William Herschel’s footsteps, Lord Rosse (1800-1867), a rich landowner and an amateur astronomer, launched in 1843 the making of a 183cm bronze mirror for his telescope, called the Parsonstown Leviathan, that can still be seen in Ireland. For this, he used a polishing machine which he described as early as 1841, for the benefit of the Royal Society.

Later on, still another amateur, a rich merchant, William Lassell (1799-1880), used a polishing machine for the creation of large-sized mirrors (notably a 122cm mirror that was set up in Malta in 1855).

|

|

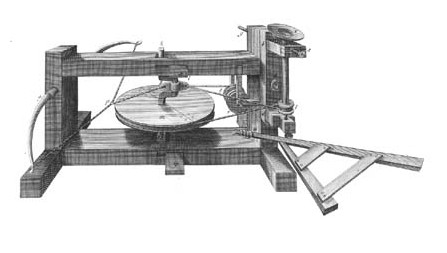

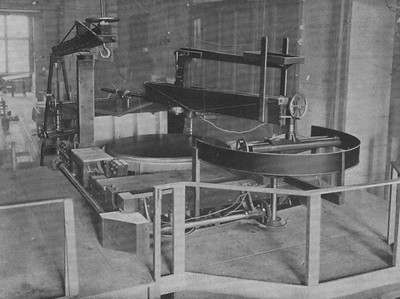

| One of William Herschel’s polishing machines (only used for carving small mirrors) | William Lassell’s polishing machine |

|

|

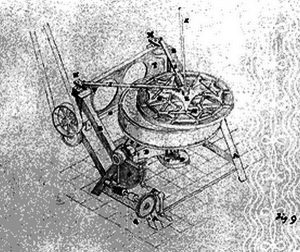

| Drawing of a polishing machine used by Lord Rosse (1841) | Polishing machine designed by Henry Draper (1850) |

But throughout this saga, we also encounter professionals : among whom Henry Draper (1837-1882) who was one of the first to carve mirrors in application of Leon Foucault studies. For this purpose, around 1850, he invented a machine inspired by the one designed by Lord Rosse in 1840, which for a long time was the benchmark. This type of machine is still known today under his name (see drawing above).

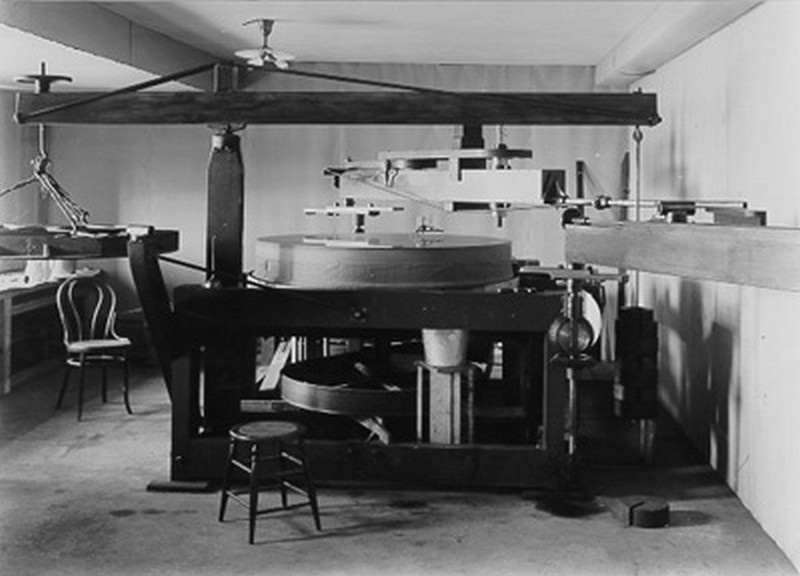

More recently, George Willis Ritchey, in his turn, improved and used the same type of machine, in the United States first (particularly for the making of the 2.5 meter mirror destined for the Mount Wilson Hooker telescope) then in France at the optics laboratory of the Dina foundation at the Paris observatory. After his stay in France, he left behind him two machines and a project for another with an 8 meter capacity, which was never built.

As for Bernhard Schmidt (1879-1935), he used another type of machine. Its movements were activated with the foot, due to his limited financial means. This fact didn’t prevent him from producing high quality mirrors though.

|

|

| 2 meters polishing machine designed by G. W. Ritchey for the Dina laboratory at the Paris observatory (from 1924) | George Willis Ritchey’s polishing machine (1890) in his workshop in the United States |

|

|

| 8 meters machine projected by G. W. Ritchey | Bernhard Schmidt’s polishing machine |

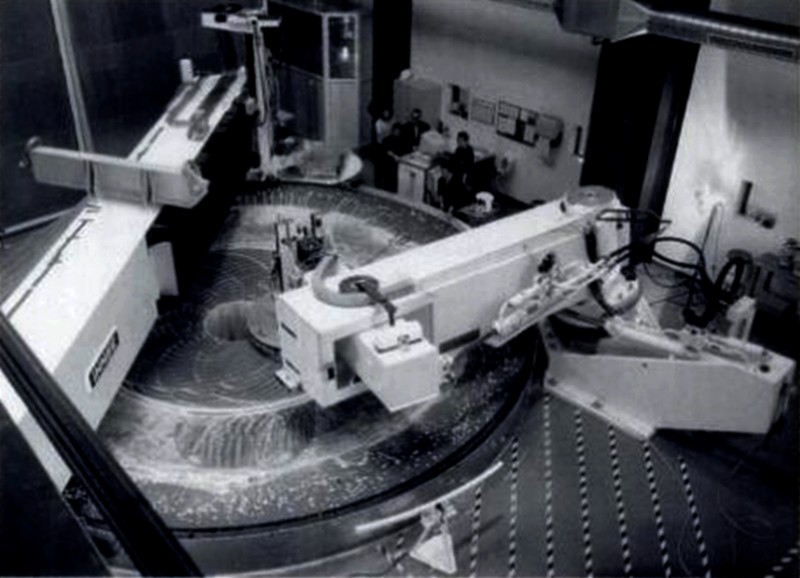

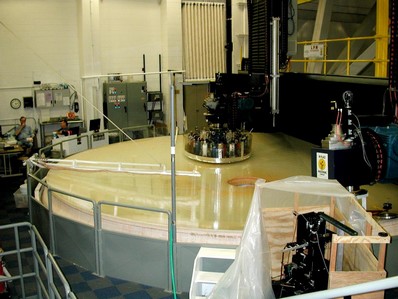

In the 20th century, with the building of large telescopes at professional observatories, polishing machines became more and more gigantic as well as more and more sophisticated. From that point of view, computer science allowed major advances with the development of revolutionary techniques perfected by specialized firms (Zeiss, REOSC,…). For instance, robots of the same type used in the automobile industry are entirely driven by computers to complete mirror polishing and figuring. This way the movements and the pressures are controlled, as are the deformations of the stand for the polishing of the mirror and of the lap (these are known as the of stressed-mirror or stressed-lap techniques). Besides, the use of such robots allows improvements of the machine’s programme following the results obtained.

|

|

| One of the mirrors of the 8′ VLT telescope during the polishing sequence (picture by REOSC – SAGEM) | Polishing operations of one of the mirrors of the Large Binocular Telescope (picture by SOML Mirror Lab) |

Early in the history of ‘modern’ amateur astronomy we can find references to the use of machines. Indeed, as early as August 1922, Paul Vincart describes one of them in an issue of the « Ciel et Terre » magazine, of the Belgian Astronomical Society (Société Belge d’Astronomie). Later on, in the 1930’s, in the United States, Albert Ingalls mentions different types of machines in his fundational book «Amateur Telescope Making». In France, one can read descriptions of such machines in an issue of the « Astronomie » magazine of the SAF (Société Française d’Astronomie) dealing with the 108 th session of the commission in charge of instruments, in February 1958. For a long time, amateur mirror makers have been exploring the positive points of machines. One can give the names of Pierre Bourge, Félix Bacchi, or, more recently, Dany Cardoen. Yet, in our country, these techniques have never been as popular as on the other side of the Atlantic. This phenomenon may be explained by the fact that the bible of French amateur mirror makers, « La construction du télescope d’amateur », written by Jean Texereau, never said a word about these tools. Thanks to the recent development of Internet exchanges, one can read many testimonials by amateurs benefitting from the community of amateur makers.

|

|

| Drawing of the machine designed by Paul Vincart, as shown in ‘Ciel and Terre’, in 1922 | Drawing by Jean Texereau representing a Draper machine and a Hindle machine, published in ‘L’Astronomie’ magazine, in 1958 |

Eventually, these machines were also used as allies by independant professional mirror makers. In France, the late Roger Mosser used one of them decades ago (see photo below). The same applies today to his followers, Franck Grière (Mirro-Sphère) and Jean-Marc Lecleire (Astrotélescope).

In the USA, one such example is Carl Zambuto, a professional who generously shares his knowledge and his techniques throughout the amateur community. We must also mention another American, Mike Lockwood, and an Italian, Romano Zen.

|

|

|

| Roger Mosser at his polishing machine (by the Photo Club of Astro d’Imphy) | Polishing machine used by Frank Grière, Mirro-Sphère | Carl Zambuto using one of his machines |

|

|

|

| A polishing machine used by Romano Zen |

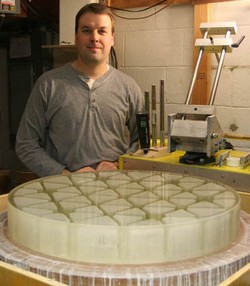

Mike Lockwood standing behind his large diameter polishing machine |

Machine used by Jean-Marc Lecleire |